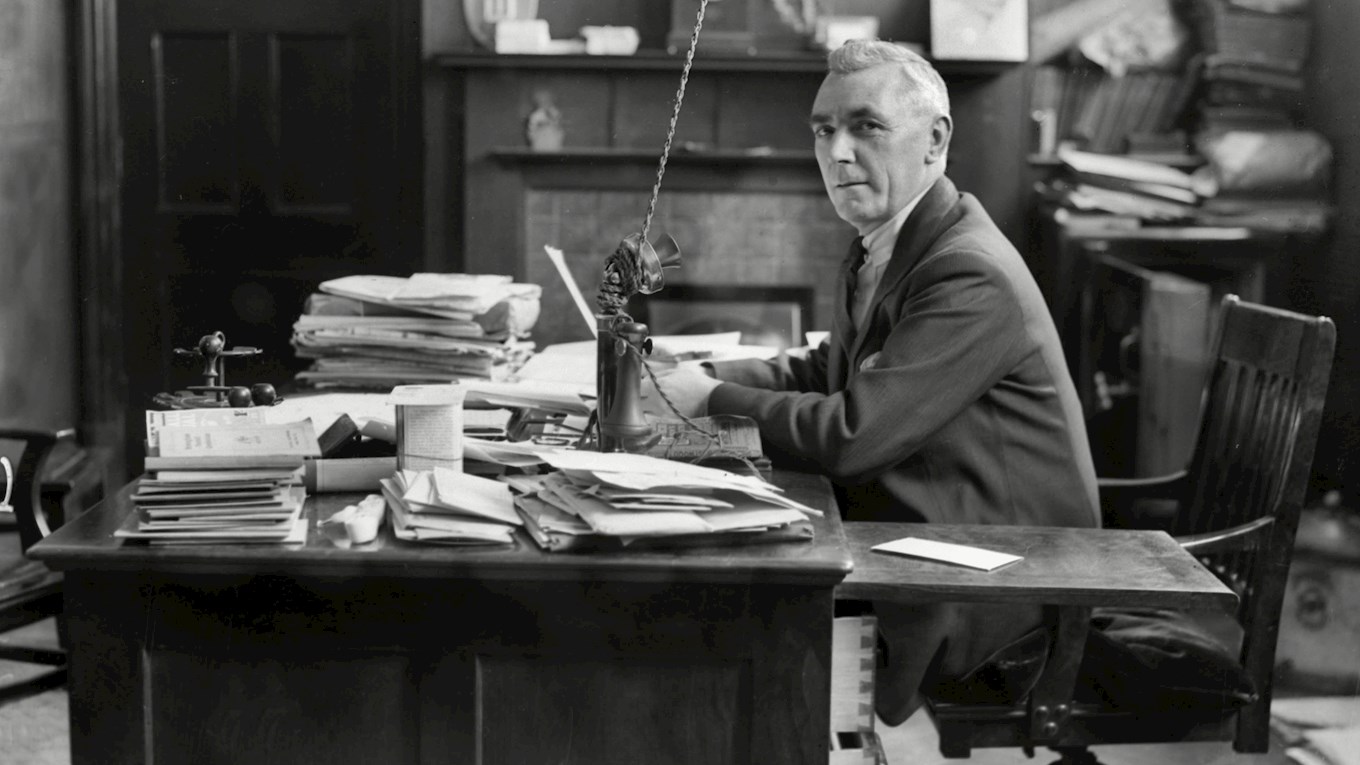

9 | INVENTING THE FUTURE: THE FRED EVERISS STORY

We talk of Billy Bassett, of Jesse Pennington, of Tommy Glidden, the great Ray Barlow and Tony Brown, and so we should. But when you want to speak of the men who mattered most in Albion’s long story, Fred Everiss’ name must ring down the ages along with all of those. For he was an Albion man, heart and soul.

It’s only right and proper that administrators keep a low profile and that the power and the glory should go to the players who produce the on field deeds that propel a club forward, create history, build a legacy. Even so, behind the scenes, the wheels need greasing, the machine needs oiling if the game is to go on, if the players are to be allowed to perform, if the club is to be able to survive and thrive. That is the job of the administrator.

During football’s infancy a century and more ago, the club secretary would also double up as team manager, although the team itself would ordinarily be selected by a committee of directors. Albion went through a number of these secretary / managers before, on the departure of Frank Heaven, we came upon a figure who was to create a dynasty, Fred Everiss taking on the role in 1902.

If some come into football today having been seduced by the apparent glitz and glamour of it all, Fred was under no illusions when he came on board as “a very perky Throstle aged 13, my wages being four shillings a week. That did not worry me for what appealed to me was that I should be able to see the matches for nothing.

“We had a ground called Stoney Lane (mind you, I have heard it called other things as well) and our offices were in High Street, up three long flights of steps which saved us from many troublesome callers who did not fancy the climb. And we did not fancy them. In those days most of the letters we received began with the word “Unless”.

“In 1900 we moved to The Hawthorns against much opposition although I think if we had stayed at Stoney Lane we would have gone out of existence. The staff – that is the boss [Frank Heaven] and I – moved there too, an office having been provided for us on the ground, and our ups and downs there for the first ten years outrivalled any scenic railway in the world.

“I was called before the directors in 1902, and although I had not asked for the job, I was appointed to succeed Mr. Heaven who had just resigned from the secretaryship of the club, and I was then aged 19”.

Everiss was fortunate to take over an Albion ascendant for the club had just won Division Two the previous season, spending only one year in the Football League’s basement before marching imperiously back to the top table. But tumultuous times were in the offing as the club lacked the quality of player that it had employed in the golden period of the late 1880s and early 1890s. Within a couple of seasons, relegation beckoned again, and though the enclosed Hawthorns was an infinitely better theatre for football, Albion’s struggles meant they weren’t drawing in the crowds they’d hoped for.

The club was on a downward spiral and in 1905, though we finished 10th in Division Two, we were a mere three points away from having to apply for re-election to the Football League. Financially we were in freefall after a series of mishaps that season, including one on Bonfire Night 1904 when Noah’s Ark, the old stand painstakingly transplanted from Stoney Lane, burnt to the ground. More than £4,000 of damage was done, while to rebuild the stand would have cost £1,600, money the club did not have, not least because the insurance payout of £951 went straight into the hands of the creditors.

By the end of the season, we were in tatters, the bank serving a writ against the board in an effort to get back the money it was owed. The board resigned, Harry Keys returned as chairman, former Albion great Billy Bassett joined the new board and Albion limped on, not least thanks to the efforts of Everiss who went cap in hand to other clubs – Aston Villa and Newcastle each donated £50 – and the Birmingham Evening Despatch who set up a shilling fund to raise £401.

Yet as Everiss recalled, it looked no more than a stay of execution. By the end of 1909/10, though results had improved on and off, we were still in Division Two. “In 1910 I had to call a directors’ meeting to decide whether we should carry on, because our financial position was such that we had been advised by experts to close down. Only one attended and that was Mr. Bassett who was chairman.

“A decision had to be made entailing all the summer expenses and finally we decided to continue, the cash being provided by Mr. Bassett, Mr. Harry Keys and Mr. Dan Nurse, neither of whom were directors just then, and myself”. Without those four men, you’d currently be doing something else with your Saturday afternoon.

The club realised they were drinking in the Last Chance Saloon now and Bassett placed his faith in his young manager, still only 27. The two took it upon themselves to completely rebuild the playing staff, understanding that Albion’s only means of survival was, as ever, via results – if we won games, people would come. It was to be expected that Bassett could spot a player, but his eye was no more finely tuned than Everiss’. They scoured the locality, asked for reports from local contacts and had the courage to act upon their convictions.

“When the [1910/11] season opened, I hadn’t a bean in the world, it had all gone to the Albion and I suppose I was a sort of super optimist. But we had a marvellous season and finished up by winning the championship [Division Two] and the club found itself with plenty of money, our debts were paid and everything was set fair again.

“A year later we reached the Cup Final and with the cheque we received as our share, purchased the freehold of The Hawthorns and so everything was, for the first time in our history, the club’s own property”.

With Everiss presiding over day to day matters alongside Bassett, Albion established themselves comfortably in the top division and, when the Great War meant the cessation of footballing hostilities at the end of the 1914/15 season, they were looking like the coming force. Everiss continued to work diligently such that when the game returned in 1919/20, Albion were ready.

The club stormed to the First Division title for the only time, racking up a record 60 points and scoring over 100 goals. It was the fulfilment of every dream that Everiss might have had for his club which, quite rightly, immediately recognised his extraordinary contribution by making him a Life Member of the club, an honour later bestowed on his son Alan too.

The workload was becoming extreme, for Everiss had team responsibilities to contend with along with scouting and signing duties, on top of which were added the administrative requirements of his post, which were yet more onerous.

Everiss was so utterly dedicated to his job and to the club that the workaholic would often put in an 18 hour day, ensuring that everything went smoothly. But in this game, it’s never quite that simple because competition must always mean there are winners and losers. In 1926/27, we were on the wrong side of the equation and relegation placed the icy fingers on the shoulder and gathered us in.