7 | FOOTBALL RETURNS AFTER THE GREAT WAR

Given football’s global domination in the 21st century, it’s sobering to recall that just over a century ago, the organised game was still in its relative infancy when it was thrown into chaos by the onset of the first global conflict, the Great War.

When it began in 1914, league football tried to stumble on, looking to maintain business as usual insofar as it could, tangled up in a web of pre-existing player contracts and other financial obligations, along with absolutely no conception of how long the war would last.

When it became clear that it wasn’t going to be over by Christmas 1914 after all, when crowds plummeted as young supporters set off for the fight and as players too began to enlist in the forces, when the sheer scale of the losses and the horrific nature of the suffering caused became everyday currency, the idea of football going on its own sweet way quickly became distasteful.

The 1914/15 season really couldn’t end soon enough and once the final ball was kicked, the game was mothballed and put into deep storage, only to be dug out again once normality had returned to the world. That normality was a long, long time in coming and the names Verdun, the Somme, Passchendaele and others would have to be etched, deep and savage, into the public consciousness before we could think again of Newcastle, Everton and Albion.

Eventually, as the summer of 1918 turned towards the autumn, there was light at the end of the tunnel and the possibility of peace beckoned from the horizon. On the home front, that exercised some minds most vigorously and wheels were set in motion to restore the national game to the forefront of the national conversation.

A fully fledged return to Football League arrangements was impossible. The war was not yet over, many players – and supporters – were still serving on far flung fields, casualties were still being suffered. Nonetheless, starved of almost any income for some three years, largely moribund football clubs were desperate to start filling the coffers once more. In consequence, regional leagues were discussed and, ultimately, begun, the Football League creating a Lancashire Section and a Midland Section to prevent unnecessary travel.

Albion made it clear from the outset that we would have no truck with such arrangements, the minutes of the August 9th 1918 board meeting noting that at the recent annual meeting of the Football League, we had “expressed the unwillingness of the Directors to allow the Club to take part in any competitive list of league games during the coming season whilst the War is on”.

This was no easy decision for like every other club at the time, we were haemorrhaging funds, but the reasoning behind it was brought savagely home at the next meeting in October when, “The Secretary reported…that he had sent a letter of sympathy to Jesse Pennington on the death of his younger brother in action in France”. While that was going on, we simply could not countenance playing a mere game.

Ultimately, the following month, the Armistice was signed and, gradually, the process of returning life to normal began in earnest for the 1919/20 season. All this was for the future of course. What mattered more immediately was getting some kind of football back onto The Hawthorns to give some entertainment to the locals and to assess the strength of our playing squad ahead of the resumption of the Football League proper that August.

We’d missed the boat in terms of the Football League and so we conferred with officials at Derby County, Aston Villa and Wolverhampton Wanderers, all of whom had also declined to play, in order to set up a small scale competition in the spring of 1919. The games were to be played for charity, the profits to be pooled and divided equally between the clubs “for distribution to charities etc as they may think fit”. And so, the first steps towards the 1919 Midland Victory League were taken.

If the destruction of the Great War had not been enough, Spanish flu was devastating already weakened populations and causing another wave of mass fatalities. It was recorded in the March minutes that both Claude Jephcott and Jesse Pennington had suffered very bad attacks of the virus and were highly unlikely to feature in any of the fixtures that ran from March 29th to April 26th, six games in all.

Indeed, there were concerns that the 35-year-old Pennington would ever recover sufficiently to play the game again. Thankfully, he was restored to rude enough health to skipper the Albion to the First Division title the following season, but neither he nor Jephcott were able to figure in the opening Midland Victory League fixtures, the first of which took place at The Hawthorns against the Wolves on March 29th 1919.

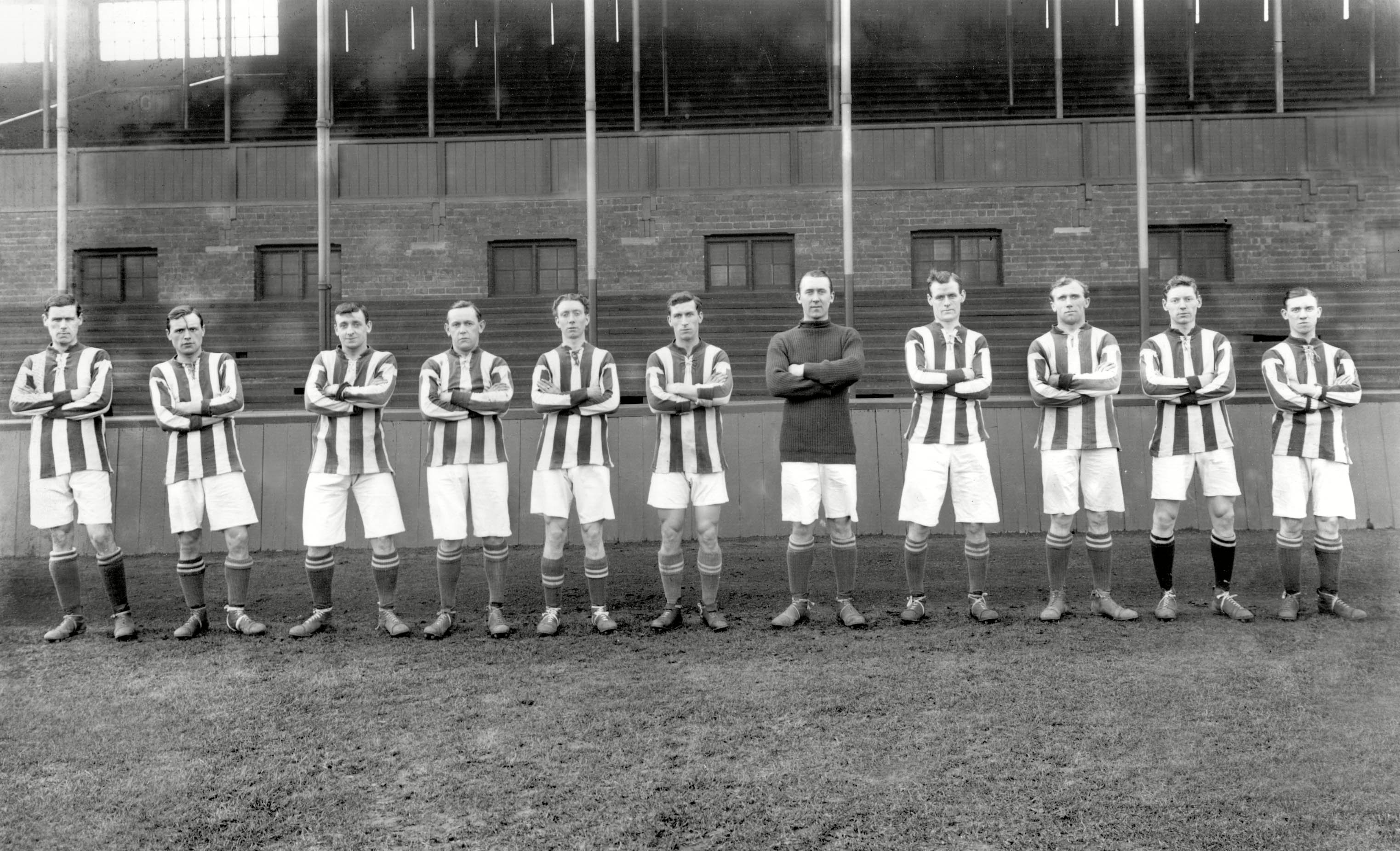

Considering the carnage that had shattered the world over those years of the Great War, Albion’s side had a remarkable familiar ring to it. Hubert Pearson, Joe Smith, Frank Waterhouse, Sammy Richardson, Jack Crisp, Howard Gregory and Ben Shearman were all there from the pre-war side and, over the course of the six games, would be joined by the returning Fred Reed, Bobby McNeal, Alf Bentley, Harry Wright, Sid Bowser, Louis Bookman and Fred Morris.

We needed them back for we started the competition on a low, losing at home to Wolves by the only goal of the game in front of 4,348 spectators. A bright start from Albion failed to yield a goal though Gregory hit the bar, and after the break, Wolves won the game with a goal from Green, though some reports suggest it was Bourne who registered the goal.

Defeat, even to the Wolves, didn’t really matter in the circumstances, for the important thing was that football had returned to The Hawthorns some three years, 11 months and five days since it had been abandoned for the duration. And we could afford to be magnanimous because when the sixth and final game came around, away to Aston Villa, Albion were still in the running to win the competition.

Played in a howling gale on April 26th 1919, the Throstles gave an indication of the whirlwind that the rest of English football should expect in the coming season, opening in imperious form to simply blow the Villa away, Edwards and Morris all but ending the game as a contest inside 22 minutes as Albion raced to a 2-0 lead. Magee duly applied the cherry to the cake with another headed goal from a Wright cross and there we were, on top of the table, the same seven points as Derby and Wolves, but with a goal average of 2.00 compared with their 1.83 and 1.50 respectively.

Perhaps there was going to be a brave new world after all…