28 | KEITH CURLE IS AN ALBION FAN…

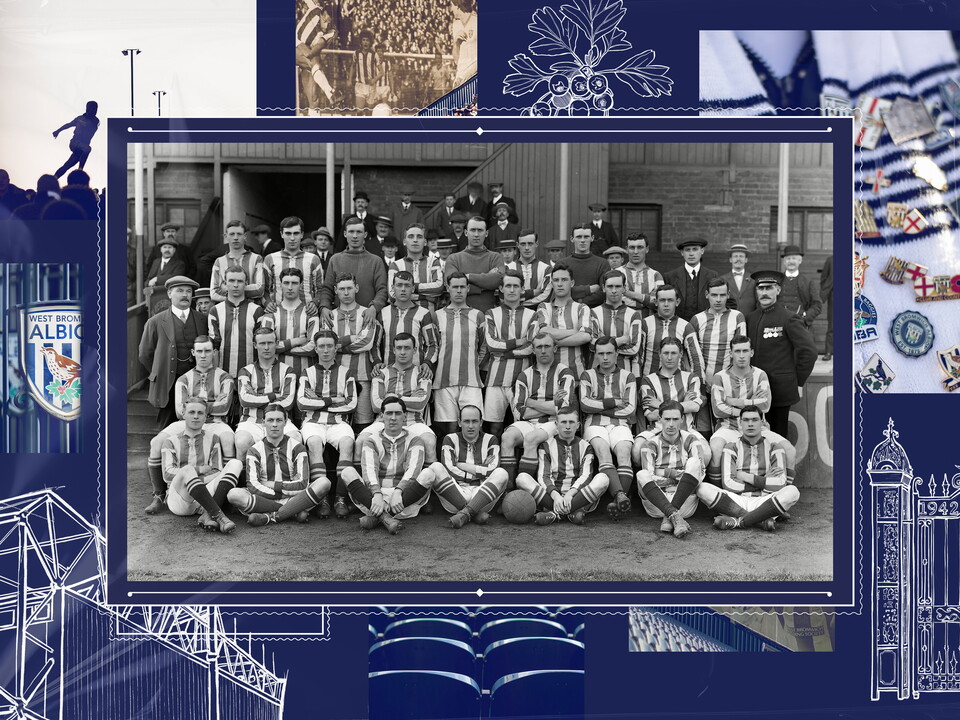

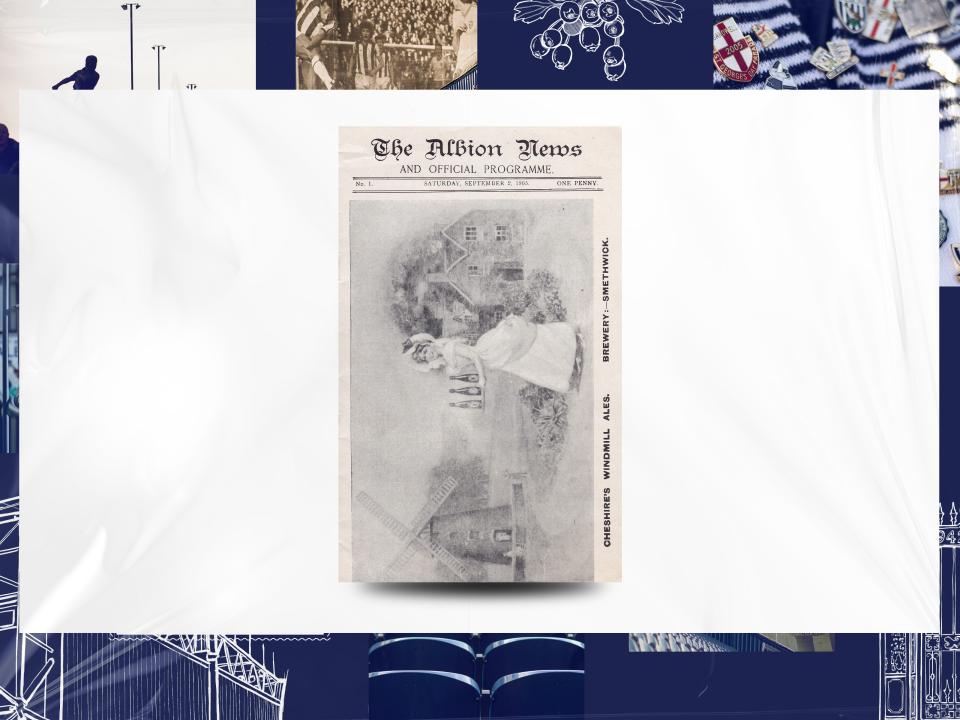

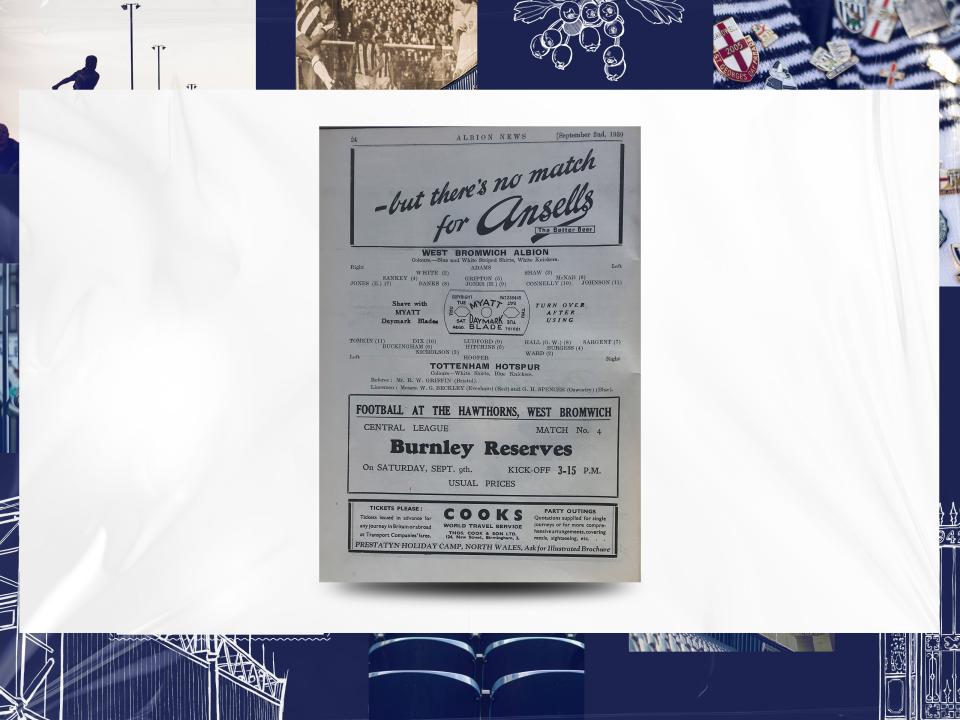

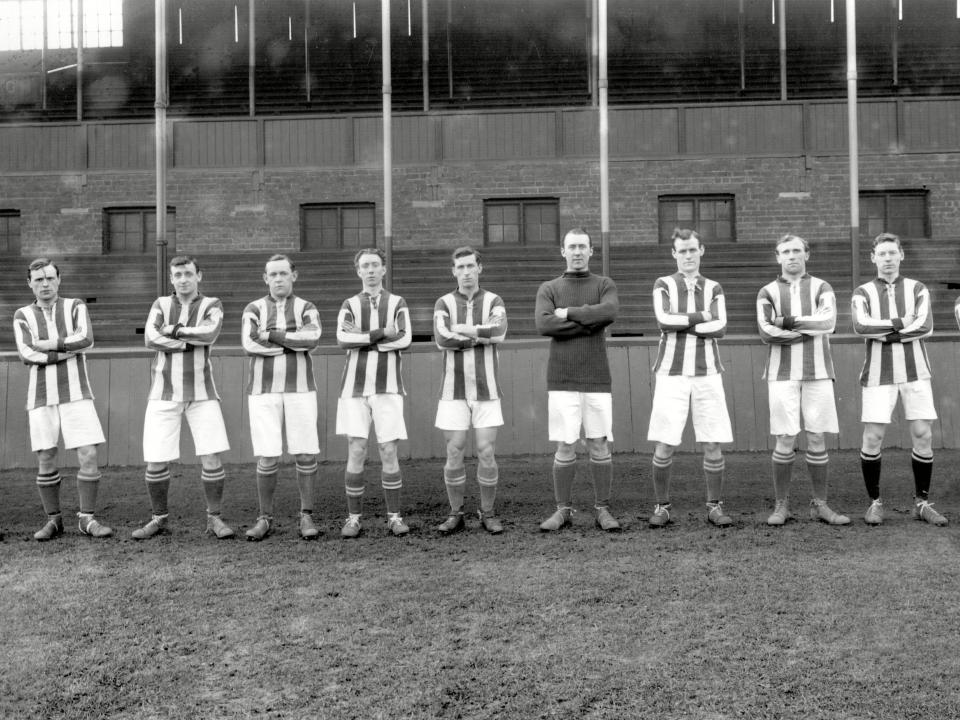

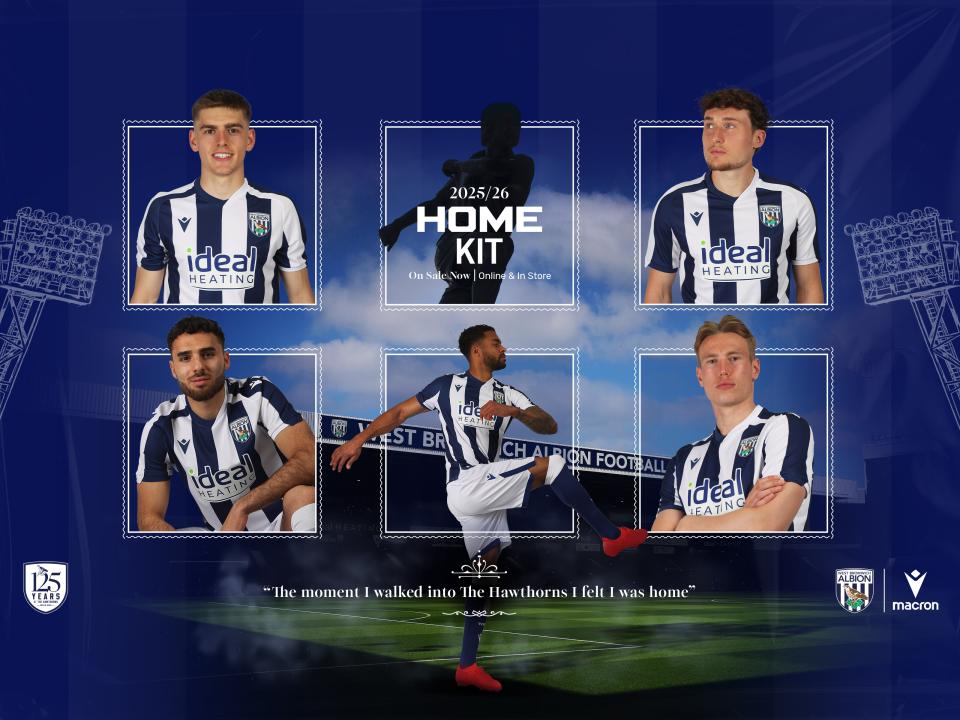

125 Years at The Hawthorns.

West Bromwich Albion are delighted to welcome you to the official platform celebrating the 125th Anniversary at The Hawthorns.

Supporters are encouraged to visit the platform regularly throughout the season for updates as we celebrate our prestigious anniversary.